Integrating Tradition, Writing a New Chapter

Jingtailan, formally known as Cloisonné Enamel on Copper, is also referred to as inlaid enamel. This intricate art involves shaping soft, flat copper wires into ornate patterns on a copper body, then filling the patterns with colored enamel glaze and firing the piece at high temperatures.

The craft flourished during the Ming Dynasty’s Jingtai reign, a period in which the technique matured and reached new heights. Due to the frequent use of peacock blue and sapphire blue enamels, the art gained the poetic and widely recognized name “Jingtailan”, literally meaning “Blue of Jingtai.”

It is now widely accepted that Jingtailan was introduced to China from the Western Regions during the Yuan Dynasty. Upon its arrival, it quickly merged with traditional Chinese culture and evolved into a distinct and refined art form—a true act of cultural reinvention.

By the Ming Dynasty, this craftsmanship had reached its golden age. It was during this time that the emperor decreed it to be reserved exclusively for the imperial court—a privilege known as “palace exclusivity.” From that moment on, Jingtailan began its destined journey as an extraordinary art form reserved solely for royal use.

Cloisonné Censer with Intertwined Lotus Motif, Yuan Dynasty

Collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing

Throughout the dynastic transitions of the Yuan, Ming, and Qing periods, generations of skilled and diligent artisans shaped the brilliant legacy of Jingtailan with their own hands. Through their craftsmanship, this art form blossomed into a shining symbol of Chinese cultural identity, renowned both at home and abroad for its distinct national style and profound cultural meaning. It is through their efforts that Jingtailan was elevated from craft to cultural heritage.

Cloisonné Zun Vase with Intertwined Lotus and Twin Lion Handles, Late Ming Dynasty

Copper-body with cloisonné enamel

Collection of the Guanfu Museum

Cloisonné Incense Burner with Intertwined Lotus and Triple-Sacrificial Knob, Ming Xuande Period

Copper-body with cloisonné enamel, double-handled

Collection of the Guanfu Museum

Cloisonné Quail Figurine, Copper-Body, Qing Dynasty, Qianlong Period

Collection of the Guanfu Museum

Large Cloisonné Ice Chest with Baoxiang Floral Motif, Qing Dynasty, Qianlong Period

Collection of the Shenyang Palace Museum

Cloisonné Floral Gu Vase with Intertwined Lotus and Flanged Rim, Ming Jingtai Period

Copper-body with cloisonné enamel

Collection of the Guanfu Museum

Cloisonné enamel is, in fact, a craft of foreign origin. In the early Ming Dynasty, Cao Zhao recorded in his seminal work Ge Gu Yao Lun (Essential Criteria of Antiquities), under the entry “Dashi Kiln” (Arabian Ware):

“Made with a copper body and decorated with colorful floral patterns fired using mineral glazes… similar to Falang (foreign inlays).”

After this technique was introduced into China, it quickly gained favor among the Chinese people. Enthusiasts and artisans began to study and replicate the craft, eventually refining and developing it into a uniquely Chinese art form.

The Radiance of Craftsmanship: Jingtailan Cloisonné Exhibition

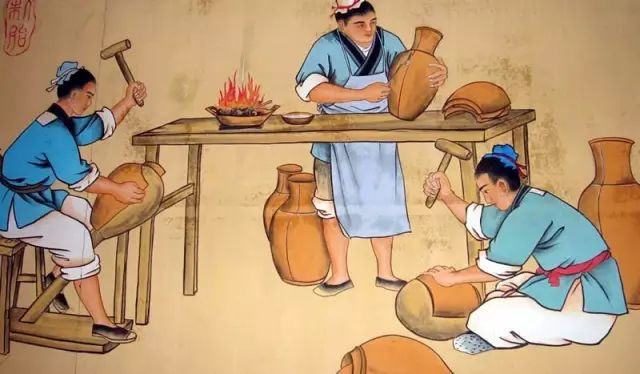

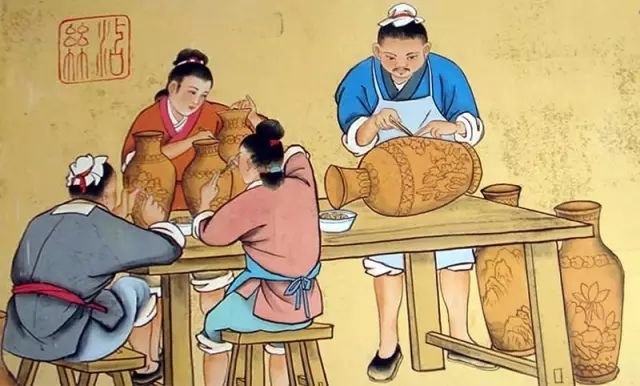

Artisans shaped sheets of purple copper into vessel bodies by hammering with simple tools, then carefully bent thin copper wires by hand to form intricate patterns of flowers and other motifs. Using small spatulas, they filled each cloisonné cell with vibrant enamel glazes, and then fired the pieces in kilns to fuse the enamel onto the copper base.

The final steps involved polishing—using a foot-powered wheel and natural abrasives like sandstone and charcoal, all done by hand to bring out the piece’s smooth, lustrous finish.

In countless workshops across the capital and its outskirts, these craftsmen devoted themselves to every stage of the process: body forming, wire setting, enamel filling, and polishing. With tireless hands and unwavering dedication, they gave rise to the brilliant cultural legacy of Jingtailan.

Cutting Copper Sheets

Hammering the Copper Body

Bending Copper Wires into Decorative Patterns

Adhering the Copper Wires to the Base

Filling the Cloisonné Cells with Enamel (Enameling)

Firing the Enamel in the Kiln

Polishing the Surface

Gilding

The cloisonné craftsmanship of the Qing Dynasty showed notable advancements compared to that of the Ming Dynasty. The copper bodies became thinner, the wires more delicate, and the enamel colors more vivid and vibrant. Surfaces were smoother, free of pitting, and the patterns grew increasingly intricate and diverse. However, the decorative motifs, while refined, often lacked the expressive vitality seen in Ming-era designs.

The peak of Qing cloisonné artistry occurred during the reigns of Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong. Among them, the Qianlong period marked a particularly glorious era, with imperial support driving technical excellence and stylistic richness. In fact, the majority of surviving cloisonné pieces seen today originate from these three reigns.

Lama Pagoda with Taotie Motif in Inlaid Enamel, Qing Dynasty

Collection of the Shanghai Museum

Bowl with Floral Scrolls and Inscriptions in Painted Enamel on Copper, Qing Dynasty, Jiaqing Period

Collection of the Guanfu Museum

Painted Enamel “Three Rams Bring Bliss” Jardinière with Wa-Style Corners, Late Qing Dynasty

Collection of the Shenyang Palace Museum

Pomegranate-Shaped Vase with Cloisonné Enamel and Chased Copper Body, Qing Dynasty, Qianlong Period

Collection of the Guanfu Museum

Cloisonné Brush Rest with Double Dragons and Sea Wave Motif, Qing Dynasty, Qianlong Period

Collection of the Shenyang Palace Museum

From Enamel Blue to Imperial Glory: Recasting Splendor

“Mountains stretch a hundred miles clad in pure hues;

White-haired elders gather at jade-filled feasts.

Honor age, not rank or birth,

Bow to the long-browed, blessed with years.

Marvel not at sovereign and subject, both in vigor—

May all people prosper together.

Though burdened with state affairs without pause,

At seventy, I still shoulder it all.”

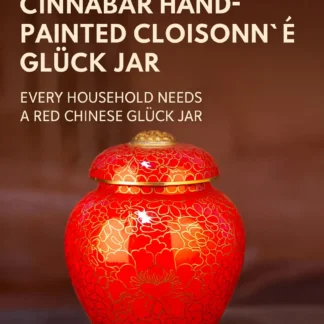

Recommended products

-

Hand-Painted Cloisonné Earrings with Natural Chalcedony – Enamel Chinese Palace Style Dangling Studs

Original price was: $24.00.$17.00Current price is: $17.00. -

Enamel Pineapple Crystal Jewelry Box – Hand-Painted Decorative Craft Ornament

Price range: $32.00 through $114.00 -

Cloisonné Enamel Tea Caddy – Handcrafted Jingtailan Jar with Filigree Detailing

Original price was: $560.00.$480.00Current price is: $480.00.

In the year 1722, after sixty years of reign, Emperor Kangxi hosted a grand imperial banquet in the Palace of Heavenly Purity on the first day of the Lunar New Year to honor the elderly of the realm. He composed this poem, “Verses for the Banquet of a Thousand Elders”, to commemorate the occasion, giving rise to the name Qianshou Yan (Banquet of a Thousand Elders).

During the flourishing era of Kangxi and Qianlong, a golden age lasting over 130 years, the Qianshou Banquet was held four times — twice by Kangxi, and twice by Qianlong.

In 1795, the 60th year of Qianlong’s reign, the 85-year-old emperor announced at the Palace of Diligent Governance in Yuanmingyuan that he would abdicate in favor of his 15th son, Prince Jia of the First Rank, Yongyan, who would ascend the throne as Emperor Jiaqing the following year.

On New Year’s Day, 1796, the year of Bingchen, Emperor Qianlong presided over the grand abdication ceremony at the Hall of Supreme Harmony, passing on the imperial seal. Jiaqing was enthroned, and Qianlong became the Retired Emperor.

Just a few days later, on the fourth day of the New Year, the now-retired “Perfect Elder” (Shiquan Laoren) held the final and most magnificent Qianshou Banquet at the Hall of Imperial Supremacy in the Palace of Tranquil Longevity (Ningshougong). The halls were filled with long-living elders — a rare and glorious gathering.

At this banquet, each elderly attendee was presented with a silver longevity plaque, decorated with auspicious ruyi cloud patterns. These plaques varied in weight depending on age, with many as heavy as ten taels. At the time, they held equivalent monetary value to silver, and over the centuries, most were melted down for reuse. Surviving examples are now exceedingly rare, and their historical and cultural significance is beyond measure.

Imperial Silver Longevity Plaque Bestowed by the Retired Emperor, Qianlong Period, Qing Dynasty

Inscription: “Bestowed by the Retired Emperor” (Tai Shang Huang Di Yu Ci Yang Lao)

Collection of the Guanfu Museum

Learn more about the Qianlong Emperor’s abdication and the Banquet of a Thousand Elders from the Palace Museum:https://en.dpm.org.cn/collections/collections/2020-03-12/2399.html