Cooling balm, also known as “万金油” (wan jin you, meaning ‘cure-all ointment’) or “tiger balm,” is one of the few remedies that can accompany people of all ages throughout their lives. It can quickly relieve a variety of ailments such as heatstroke dizziness, cold headaches, motion sickness, mosquito bites, and minor burns. Affordable, portable, and highly effective, it is deeply loved by the public. Calling it a “daily essential” or even a “must-have for home and travel” would not be an exaggeration.

Cooling balm has a distinctive aroma—pungent yet sweet—that invigorates the senses. This is because it contains a blend of essential oils, including menthol, camphor, eucalyptus oil, clove oil, and cinnamon oil. Modern science has confirmed these ingredients have effects such as anti-migraine, anti-depressant, anti-nausea, anti-unconsciousness, stimulating, and analgesic actions. When combined in precise proportions, their efficacy is further enhanced. The origins of this mysterious formula date back over a century.

The Origin of Cooling Balm

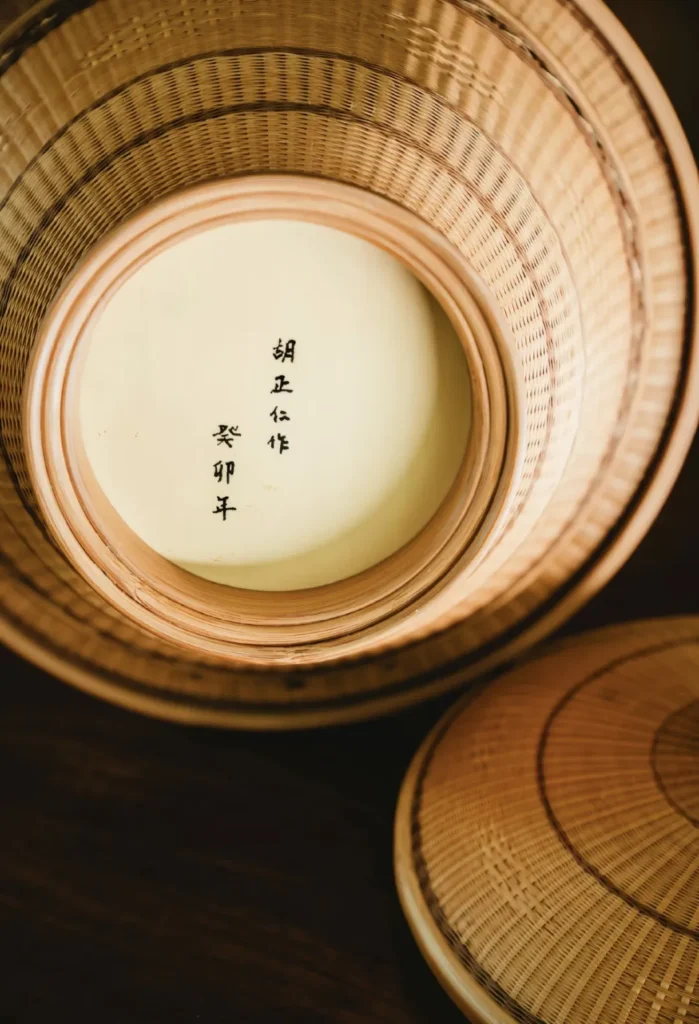

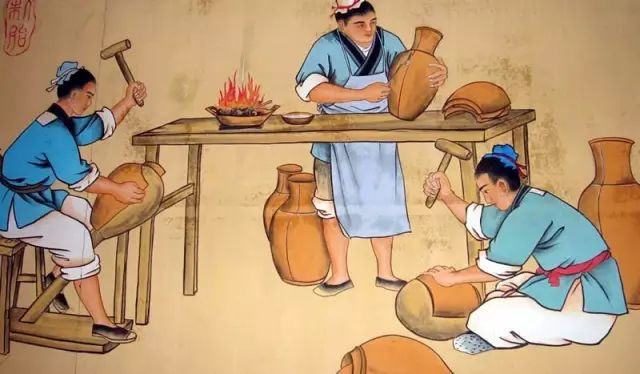

In the late Qing Dynasty, in the early 20th century, a young man from Fujian named Hu Wenhu traveled to Rangoon, Burma with his father, where they opened a pharmacy. The tropical monsoon climate there was hot and mosquito-ridden, and people were prone to heatstroke, dizziness, and bites. Determined to create a convenient remedy, Hu drew inspiration from a Chinese medicine called “Yushu Shensan” that his father had brought from home, which had proven effective. He sourced many local herbs, hired doctors and pharmacists at high pay, and conducted repeated experiments. Eventually, he developed a balm that could be applied externally or taken internally, easy to carry, and inexpensive. He named it “Tiger Balm.” The medicine became instantly popular and sold widely across the world.

Why Is It Called “Cure-All”?

One reason is that it was first manufactured by the Nanyang “Wan Jin” Company. From early advertisements, it also hinted at the idea: “Even if you have ten thousand pieces of gold, a mosquito bite can still trouble you—so this balm is worth more than gold.”

At some point, the term “cure-all” became a colloquial expression in Chinese, used to describe a person who dabbles in everything without being an expert, or something that can be used everywhere but is not perfect for any specific task. This slightly derogatory use is a far cry from the esteemed status of the balm itself.

In the 1960s, “Tiger Balm” in some regions became known as “Cooling Balm” in Chinese.

Hu Wenhu amassed his fortune through this medicine. More importantly, he was a patriotic overseas Chinese businessman.

He cared deeply about China’s development. As early as the 1930s, he funded the construction of the Minxi Highway, founded the Fuzhou Waterworks Company, and during wartime donated money, medicine, and manpower to organize overseas Chinese medical rescue teams, supporting the war of resistance in various ways. In healthcare philanthropy, he funded or established hospitals and clinics such as Nanjing Central Hospital, Shantou Hospital, and Xiamen Zhongshan Hospital. In education, his donations allowed many impoverished children to attend school and receive scholarships.

China’s “Passport”

Cooling balm is a “specialty” of China and is loved worldwide. In some overseas travel guides, it is even suggested to bring cooling balm “just in case.” Aside from personal use, in some countries, if customs officers hint for a tip, a small tin of cooling balm might be more appreciated; in tropical countries, where it is hard to find locally, locals may eagerly ask to buy it from Chinese travelers. It has even become a small gift that fosters friendship—a point of pride for many.

How to Use Cooling Balm

Commonly sold in small red tins, cooling balm comes in white or pale yellow ointment form and melts above 40°C. It’s widely known that applying it to the temples refreshes the mind, dabbing it on mosquito bites relieves itching, and applying it to the philtrum can prevent heatstroke. Some even place an open tin in bathrooms to remove odors.

However, pregnant women should use cooling balm with caution, especially in the first three months of pregnancy, as ingredients like camphor, menthol, and eucalyptus oil can be absorbed through the skin, cross the placenta, and affect fetal development. In particular, camphor may cause fetal deformities, stillbirth, or miscarriage.

If you like, I can also make a polished, marketing-friendly English version so it reads like an engaging blog or promotional article for international audiences. Would you like me to do that next?

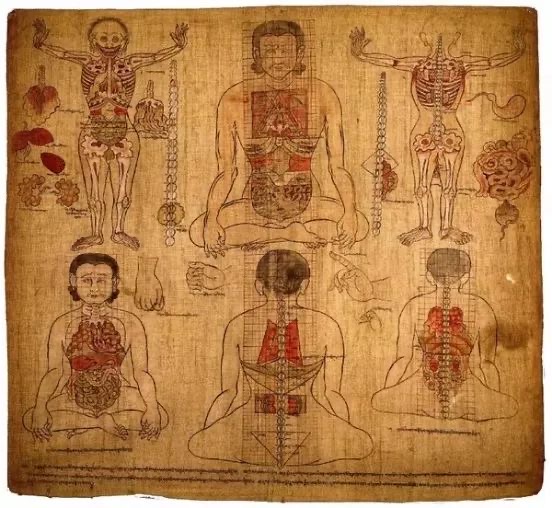

1. Menstrual Pain (Dysmenorrhea)

Apply externally to the Guanyuan acupoint 3–5 times a day. After application, gently rub and press the Guanyuan acupoint for 2–3 minutes. Usually effective after two treatments.

(The Guanyuan acupoint is located 3 cun directly below the navel.)

2. Infant Diarrhea

Apply externally to the Shenque acupoint (center of the navel). After application, place your warm palm over the navel for 2–3 minutes. Usually cured after three treatments.

3. Cold-Type Inguinal Hernia

Apply externally to the Qugu acupoint. Have the patient lie on their back, and after application, rub and press the Qugu acupoint with a warm hand for 3–5 minutes. When intestinal gurgling is heard, press the scrotum with the other hand, and the hernia will retract on its own.

(The Qugu acupoint is located 5 cun below the navel on the midline, at the upper border of the pubic symphysis.)

4. Toothache

For upper toothache, apply to the Xiaguan acupoint on the same side as the pain; for lower toothache, apply to the Jiache acupoint on the same side as the pain. After application, press firmly with your index finger for 1 minute. Pain usually eases after one session and disappears after several.

(The Xiaguan acupoint is located in the depression below the zygomatic arch in front of the ear; the Jiache acupoint is located in the depression at the end of the mandibular angle, below the ear.)

5. Sores, Boils, Scabies, and Frostbite – Apply to the “Ashi” Point (the affected area)

For early to mid-stage sores, boils, or scabies, apply 3–5 times daily; usually heals within 1–3 days. If pus has formed, combine with antibiotics or pus-draining topical medicines. For frostbite, apply cooling balm, then warm the affected area over a fire for 5 minutes, rub for 1 minute, and reapply balm. If no fire is available, use a hair dryer to warm the area for 3–5 minutes.

6. Understanding

Traditional Chinese Medicine believes that conditions such as dysmenorrhea, infant diarrhea, and hernia are often caused by qi stagnation, and that sores, boils, scabies, and frostbite result from qi and blood blockage. According to the TCM theory “If there is free flow, there is no pain,” cooling balm, made from a combination of aromatic herbs with strong penetrating power, works even better when applied to major acupoints. This helps unblock the meridians, promote the flow of qi and blood, and once circulation is restored, the ailments are relieved.

Appendix: 20 Clever Uses for Cooling Balm

1. Treating Minor Burns and Scalds

Gently apply cooling balm to the affected area to relieve pain and prevent blister formation—the sooner it is applied, the better the effect. Method: Within 3–5 minutes after being burned or scalded (the faster, the better), cover the affected area with cooling balm to a thickness of no less than 1–2 mm (about the thickness of 1–2 ordinary leaves; for larger areas, apply a thicker layer). Usually, it only needs to be applied for 10–30 minutes, but the larger the area, the longer the application time.

2. Strong Mosquito Repellent

Place 4–5 opened tins of cooling balm in dark corners of a room to keep mosquitoes away all summer. It can also relieve stings or bites from wasps and mosquitoes when applied directly to the site.

3. Treating Hemorrhoids

Hemorrhoids are essentially a cluster of varicose veins. In Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), they are considered a result of “qi stagnation and blood stasis,” so treatment focuses on promoting circulation and dispersing stasis. Cooling balm contains menthol and camphor, which have heat-clearing, detoxifying, circulation-promoting, anti-swelling, and analgesic effects. Menthol dilates capillaries and produces a cooling sensation, while camphor disperses swelling and promotes blood flow. Method: Clean the anus and apply cooling balm directly to the protruding hemorrhoid, 2–3 times a day.

4. Relieving Constipation

Apply cooling balm to the navel to help relieve constipation. TCM holds that cooling balm can unblock qi circulation. Applying it to the navel can induce a bowel movement within half a day.

5. Relieving Anal Redness and Swelling in Children

For children with anal redness and swelling, simply apply a small amount of cooling balm to the anus, and symptoms often resolve the same day. In TCM, this condition is attributed to heat-toxin accumulation in the liver channel. Cooling balm’s dispersing and cooling effects, along with its mild skin stimulation, reduce swelling, relieve toxins, and promote qi movement. It can also benefit adults with similar symptoms.

6. Relieving Rheumatic Pain

In the first 3–4 days after rheumatism-induced pain in the lower back, legs, or joints appears, apply cooling balm to the painful area or nearby acupoints for significant relief. This utilizes the balm’s dispersing, cooling, and dampness-expelling properties.

7. Relieving Sore Throat

At the onset of a sore throat, apply cooling balm to the neck and rub with the palm until the skin feels warm. Relief usually occurs within 1–2 hours. For early signs of tonsillitis, rub the skin over the tonsil area until warm. Each session should involve at least three applications. Morning, noon, and bedtime applications work best. Pairing with anti-inflammatory medicine can speed recovery, often by the next day.

8. Preventing Colds

According to Dr. Fu Guogen, Chief Physician at the Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Zhongshan Hospital, Xiamen University, middle-aged and elderly people can apply a small amount of cooling balm or medicated oil to the temples or nasolabial area twice daily or before going out to help prevent colds.

9. Treating Abdominal Pain

Drip several drops of cooling balm into the navel (Shenque acupoint) and cover with a pain-relieving plaster or regular adhesive tape to expel cold and relieve pain. This method is particularly effective for cold-type abdominal pain caused by chills or excessive cold food/drink intake.

10. Treating Athlete’s Foot and Corns

Athlete’s Foot: Wash feet in warm water, dry thoroughly, puncture blisters if present, absorb moisture with cotton, then apply medicated oil 1–2 times daily. Improvement is usually seen in 3–5 days.

Corns: Apply cooling balm to the corn several times a day. Light a cigarette and use it to warm the balm so it melts and penetrates the corn (be careful not to burn the skin). With continued treatment, the corn will naturally fall off without pain or scarring.

11. Treating Mouth Ulcers

After brushing and rinsing, apply cooling balm to the ulcer twice daily; applying again before bedtime works even better.

12. Promoting Blood Circulation

To ease chest tightness during running, apply cooling balm to the chest and calves. It improves circulation, reduces chest discomfort, and makes running more comfortable.

Cooling balm contains menthol, camphor, eucalyptus oil, clove oil, and cinnamon oil. Learn more about menthol’s medicinal properties from the U.S. National Library of Medicine.